What I learned during my internship at E4TheFuture

by Owen Connolly

Prior to my summer internship, I had some knowledge of the clean energy industry, but knew nothing about distributed energy resources (DERs) and the benefits they can provide. The valuation team of Julie Michals and Shayna Fidler quickly brought me up to speed on the National Standard Practice Manual for the Benefit-Cost Analysis of Distributed Energy Resources (NSPM for DERs), as well as the Database of Screening Practices (DSP). While the DSP provides details on state cost-effectiveness practices for energy efficiency, my task was to research where and how states are valuing other DERs – with a focus on non-energy benefits (NEBs).

The research purpose was twofold: to inform a current National Energy Screening Project being undertaken to document methods for quantifying DER impacts; and to help inform whether to expand the DSP to include other DERs. With this purpose in mind, I launched my effort to learn how states account for non-energy benefits for various types of DERs.

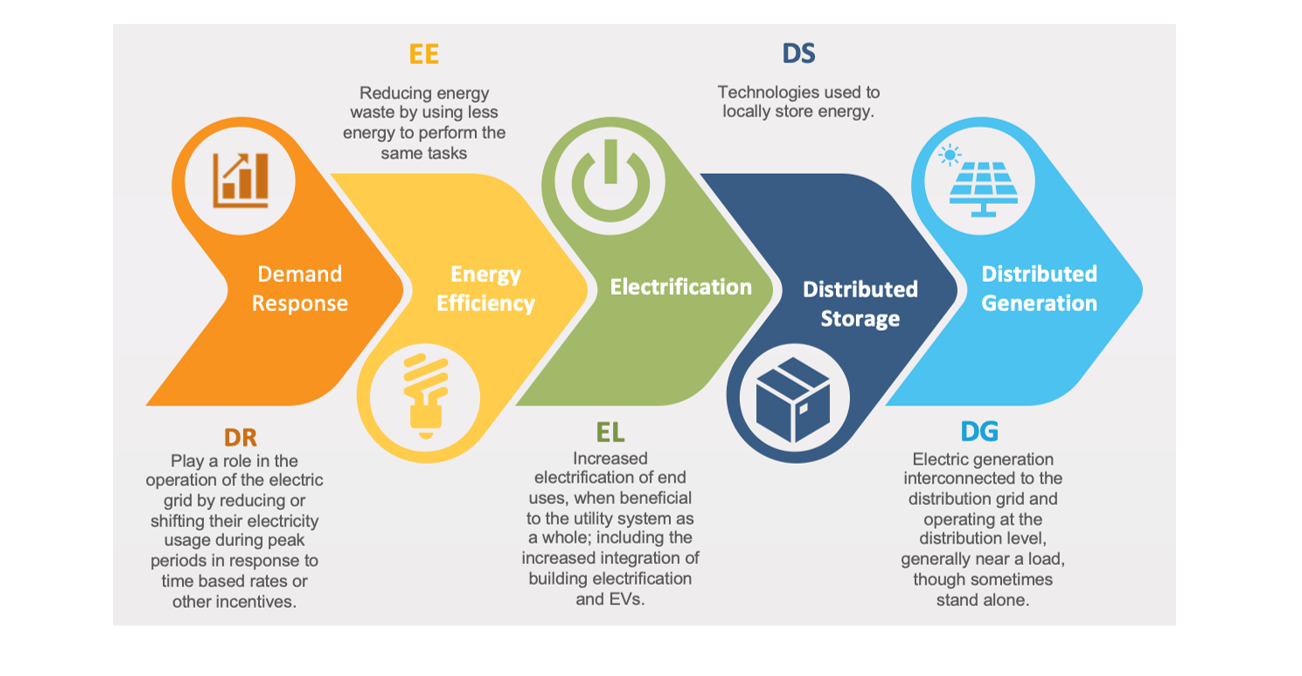

Distributed energy resources are smaller generation technologies often located close to where energy is consumed (unlike large power plants that produce energy for large geographic areas). There are different types of DERs, including energy efficiency (EE), demand response (DR), distributed storage (DS), building and transportation electrification, and distributed solar generation (DG).

Jurisdictions are increasingly looking to DERs to help meet energy needs and specific policy goals – such as reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, increasing resilience to the utility system, and more. And as energy production (and transportation) begins to shift away from fossil fuels, it’s important to account for the relevant benefits and costs of DERs in order to avoid over- or under-investment in any one resource to meet a jurisdiction’s goals (see NSPM for DERs guidance).

A Little Background on Non-Energy Impacts

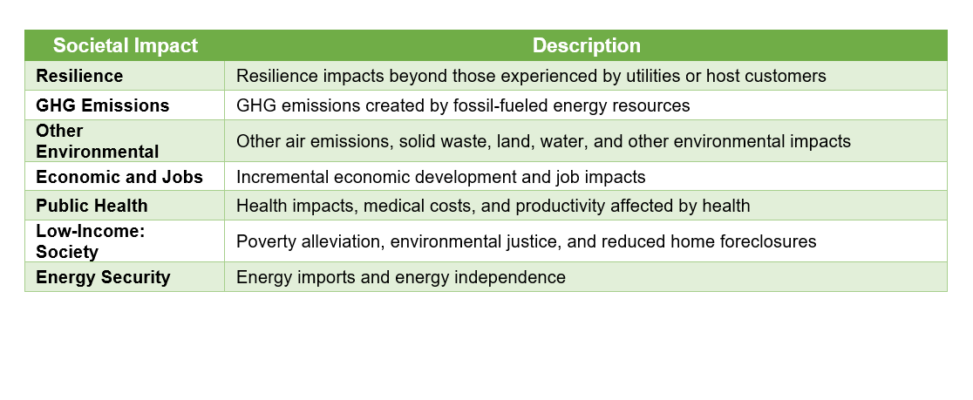

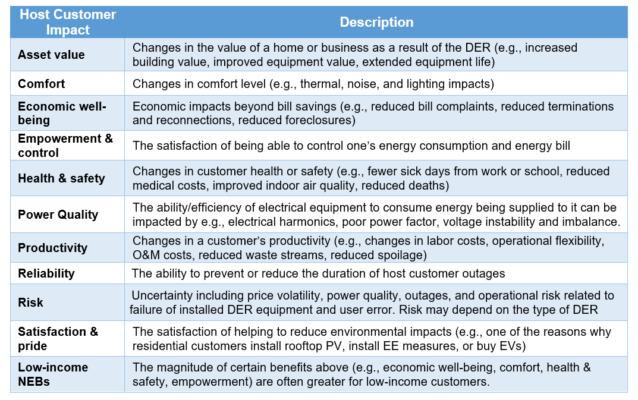

As defined in the NSPM, non-energy impacts (NEIs) are “impacts of DERs other than direct energy and demand impacts. While these impacts can be non-energy benefits and related costs, most are considered benefits.” Non-energy benefits are primarily realized by either host customers (e.g., program participants) or more broadly by society. The tables below describe the range of NEBs.

My research identified the frequency of NEBs cited for different types of DERs in a selection of reports and state regulatory dockets, and the extent to which the sources describe a method(s) used to quantify the benefits.

My Sources of Data

When I first began looking for sources of data, I focused on searching state regulatory dockets to determine where and what states have specific policies on BCA for the range of DERs. A main source I used was the PowerSuite database (developed by Advanced Energy Economy), where I could find relevant documents (e.g., utility plans, studies, public comments) by searching key words. I was able to find some information on how states currently value non-energy benefits of DERs for one or more DERs (beyond energy efficiency), but I found that state experience is limited. I had to broaden my research to reviewing general reports, using sources published by, for example, the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA), the NYU School of Law, and Clean Energy States Alliance (CESA).

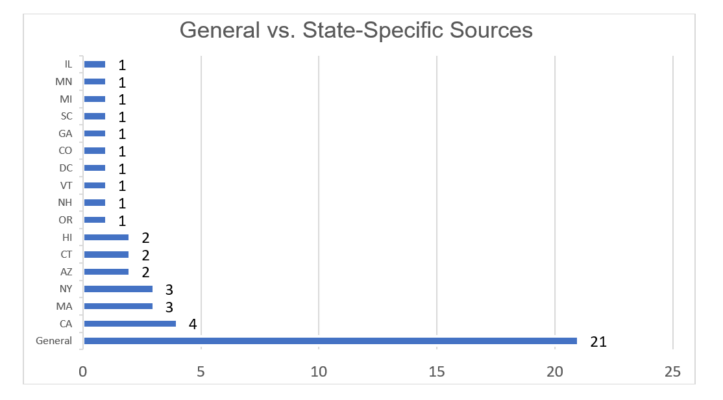

I reviewed 47 sources that referenced non-energy benefits of one or more DER types. While not an exhaustive list of sources, about half were state-specific while the balance were general (or non-state specific) reports, as shown below. For example, the report from the NYU School of Law identified four non-energy benefits: increased resilience, improved public health, reduced GHG emissions, and other environmental benefits such as local pollution.

While most states do not have regulations on BCAs for DERs broadly, or for even a few DERs, several states identify NEBs for various DERs such as in California (CPUC Avoided Costs for Valuing DERs), New York (NYSERDA VDER Stack), and Massachusetts (Investigation into DER Planning).

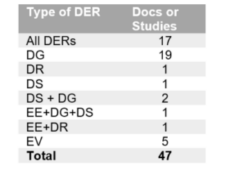

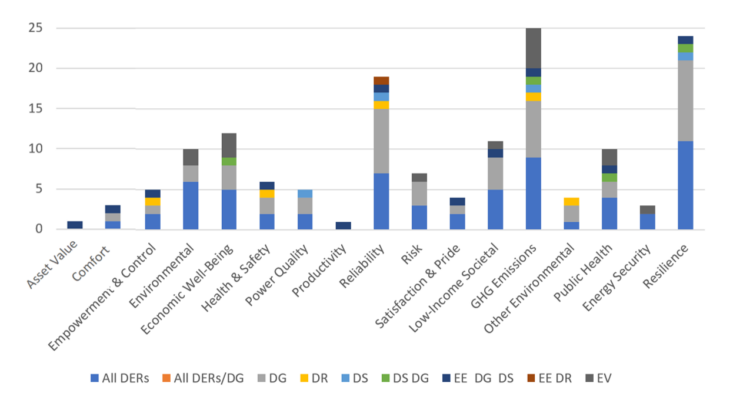

My research shows that most studies/documents that address NEBs for DERs either cover all DERs, or focus on distributed generation, as shown in the table. Studies on transportation electrification or EVs was the next most common DER report that identified NEBs. Several sources focused on 2 or 3 DER types. Going a step further, we can see how many times each NEB was cited and the corresponding DER in each report.

Because many states have carbon reduction goals, it makes sense that GHG emissions impacts are assessed as part of DER valuations. According to C2ES, 23 states have executive and legislative carbon emissions reduction goals. Reliability and resilience are also commonly identified in studies, and increasingly correspond with climate change impacts. These impacts may be more prominent in the research due to increased fear of climate change effects and pressure on energy and electric systems. The surge of forest fires this year on the West Coast and the Texas power crisis following harsh winter storms display the need for increased resilience. (As I write, Hurricane Ida has left New Orleans without power, creating health risks, disrupting transportation, contaminating the water supply, and leaving nearly $95b in damages by some estimates.) Natural disasters are expected to increase in frequency and severity as climate fluctuations disrupt weather patterns, making resilience benefits increasingly necessary when valuing DERs.

Reliability refers to maintaining generation, transmission, and distribution system to withstand instability, uncontrolled events, cascading failures, or unanticipated loss of system components. Resilience allows utilities, communities, and customers to anticipate, prepare for, adapt, respond, and recover quickly from disruptions such as hurricanes or forest fires. (NSPM for DERs)

NEBs Per DER Type

What do studies say (and not say) about methods?

My research also involved reviewing which DER studies and reports include guidance on methodologies for calculating specific non-energy impacts. Less than half of the studies (21 of the 47) included some guidance on methods for quantifying NEBs. For example, there are several ways noted in the data to calculate the value of reduced carbon emissions. The most common is using the Social Cost of Carbon.

What is Social Cost of Carbon (SCC)?

In short, the SCC is an estimate of the economic damages from emitting one more ton of CO2 into the atmosphere. However, when it comes to the actual dollar amount, the SCC is highly contested. Many states do not use the SCC to calculate the benefits from reducing GHG emissions. The ones that do, however, vary in value from $20/ton to $100/ton.

The NSPM for DERs can be useful in providing general guidance on different approaches to quantifying impacts, including those that are hard to quantify. However, recognizing the need for more detailed guidance on quantifying DER impacts, NESP is actively developing a comprehensive ‘handbook’ on Methods & Tools for Quantifying DER Impacts. This resource – coming in early 2022 – will address methods for utility system impacts and non-utility system impacts, including non-energy host customer and societal benefits for the full range of DERs. The 21 sources I found with methodologies for quantifying NEBs will help inform the forthcoming Methods & Tools handbook, which is being led by Synapse Energy Economics.

Is the DSP ready for expansion to other DERs?

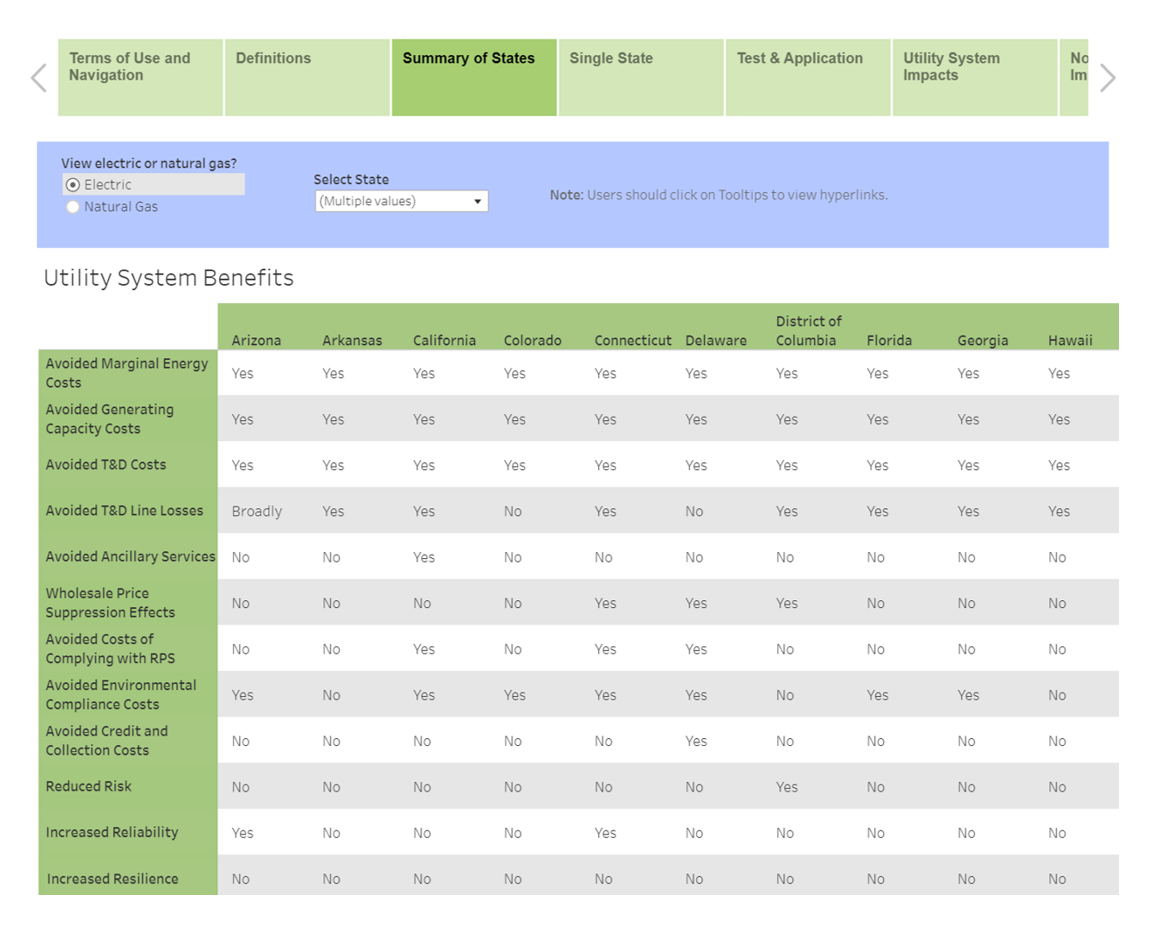

My research project investigated the possible expansion of the DSP to include information on cost-effectiveness practices for other DERs beyond electric and natural gas efficiency. I found that there do not appear to be enough states with established practices for the full range of DERs at this time. But there are many states with open investigations into the valuation of various DERs. I expect over the next couple of years we will see more states establishing requirements for the BCA of DERs. The DSP would be a richer and more useful resource if more data were added to capture other DER impacts (see below; current DSP page for energy efficiency). Hopefully states will consider using the NSPM to make sure a consistent BCA framework is used to value the different kinds of DERs.

My research helps provide a look into current trends in the DER valuation space, and in particular for non-energy benefits. While states increasingly account for NEBs—such as emissions reductions, resilience, and reliability—additional research is needed to document the full range of NEBs relevant to a state’s policy goals. And while there are quite a lot of DG valuation studies (since solar has been around for a few decades), more research is needed to value NEBs for technologies like electric vehicles, building electrification and battery storage—especially those NEBs that reflect the policy goals of the jurisdiction making the DER investments.

Database of Screening Practices – Energy Efficiency Utility System Benefits (sample page)

For more information contact NESP.

–Owen Connolly was an intern at E4TheFuture during the summer of 2021