by Shayna Fidler, Julie Michals, and Devin Hubbard

Recent news headlines are dominated by stories of growing investments in distributed energy resources (DERs). “Utility to Jump Start EV Charging Infrastructure,” “Flexible DERs to Replace Natural Gas Peakers,” and “Doubling Down on Energy Efficiency to Fight Climate Change” are becoming common topics. As the shift to a cleaner, more flexible electric grid expands in the US, the connection between investing in DERs and the associated economic development impacts is critical to building a competitive and sustainable clean energy industry.

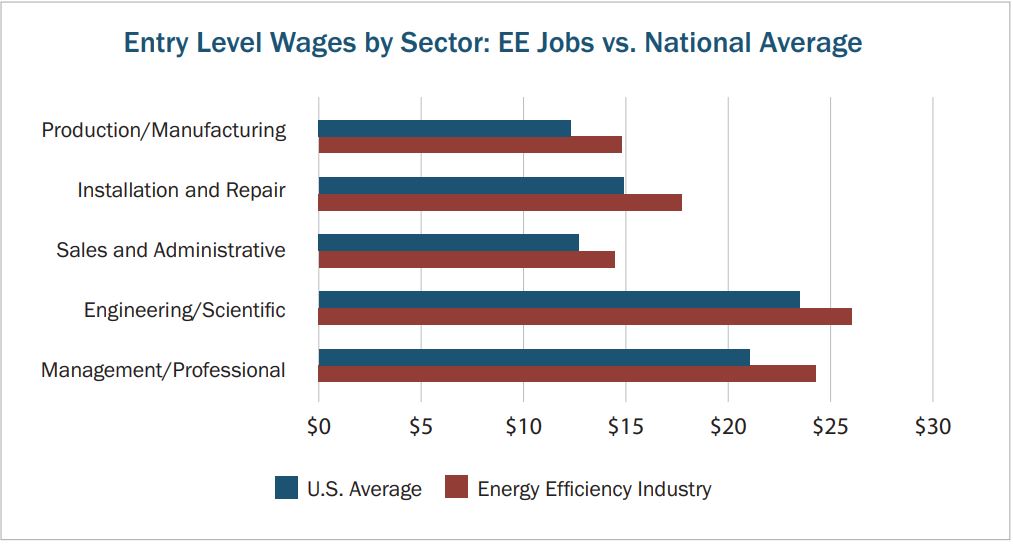

The creation of good-paying jobs in the energy efficiency and other distributed energy sectors has been clearly documented in recent reports published by E4TheFuture and NASEO and EFI. As states look to investing in DERs with creating jobs in mind, measuring these impacts is essential, but is not always easy or straightforward.

In this blog, we share some insights on experiences and approaches to accounting for economic development in the context of energy efficiency cost-effectiveness assessments, with applicability to DERs more broadly. We offer suggestions for states to consider, pointing to guidance from the National Standard Practice Manual for Benefit-Cost Analysis of DERs (NSPM for DERs).

Jobs in the energy efficiency industry consistently pay higher than the national average for jobs in America. (Source: Energy Efficiency Jobs in America. E4TheFuture. November 2020.)

Economic development is broadly defined as the impact an investment has on the local or larger economy. According to ACEEE’s Policy Brief on Measuring Economic Development Benefits (“ACEEE Policy Brief”), aspects of economic development include both direct and indirect jobs created from energy efficiency investments and any additional benefits such as increased industry investment and business productivity.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Helpful Definitions

Direct Jobs: Actual, full-time equivalent (FTE) positions created by a program or project.

Indirect Jobs: Producers of raw materials or services needed to implement a program or project.

Induced Jobs: Jobs and economic activity created when newly hired workers from direct and indirect jobs re-spend their earnings on goods and services.

Net Jobs: The number of jobs created minus the number of jobs lost in the same sector.

FTEs: Full-time equivalents; the number of hours a full-time employee works in a week, typically 40 hours.

Sources: ACEEE Policy Brief and the NSPM for DERs

__________________________________________________________________________________

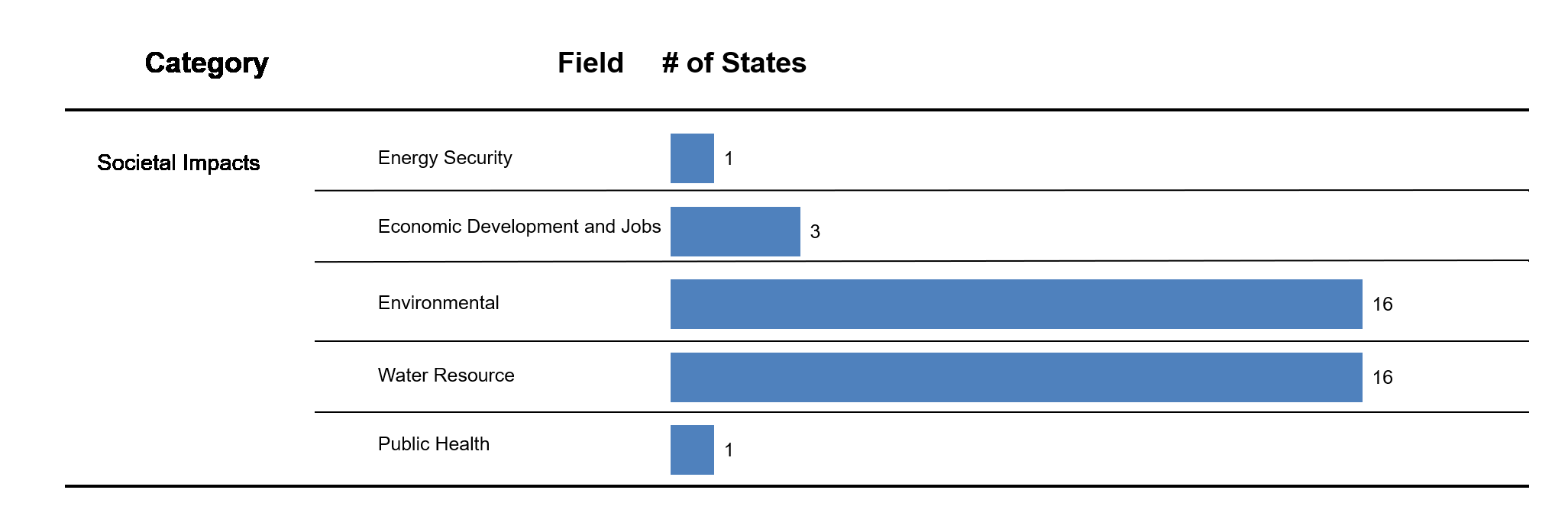

In states where policies identify economic growth as a benefit of investing in DERs, this impact should be accounted for in benefit-cost analyses (BCA). However, we see that this is rarely the case in practice. As seen below, the Database of Screening Practices (DSP) shows that only three jurisdictions currently account for economic development in their BCA of energy efficiency investments (EE). Yet according to our review of EE resource standard policies, quite a few states identify economic development as a goal in their statutes (see National Conference of State Legislatures). (Even fewer states account for energy security and public health benefits, a topic for another blog…)

Database of Screening Practices, 2021

The three jurisdictions that account for economic development are Nevada, the District of Columbia, and Rhode Island, where the approaches used to quantify these impacts vary from the use of proxies (e.g., adders), multipliers, and input-output models (or some combination thereof). Below, we briefly explore how these different jurisdictions quantify these impacts.

Let’s start with Nevada and the District of Columbia. In both cases, a proxy in the form of a percentage adder is used.

Nevada uses a percent adder to inform its 2018 Demand-Side Management Plan. The state uses a 10-25% adder to account for non-energy benefits based on whether the cost-effectiveness test applies to commercial or residential (low-income, non-low income, or a mixture of programs). Economic development is one of ten benefits included under the umbrella of non-energy benefits, so the adder is very broad. The adders were developed in consultation between stakeholders and the NV Energy Company. Due to the broad nature of “non-energy benefits” that lumps together a full range of benefits, it is impossible to know just how much economic development has an impact on the cost-effectiveness of the program portfolio.

Types of Societal Non-Energy Benefits. Image: Shayna Fidler.

When Washington D.C.’s Department of Energy and the Environment contracted with the DC Sustainable Energy Utility (DCSEU), they established a clear goal to promote workforce development through the generation of “green-collar” jobs in energy efficiency programs. As such the DCSEU BCA framework provided in the DOEE/DCSEU contract includes a simple 5% proxy adder to account for macroeconomic benefits (as well as other non-energy benefits). This means, for every dollar spent on an energy benefit, five cents will be added to the BCA to account for the macroeconomic benefits.

The advantages to using percentage adders are that they are relatively easy to derive, potentially saving time and technical research. According to a Northeast Energy Efficiency Partnerships report, adders are not necessarily developed using direct observations, rather are built upon the practices of surrounding jurisdictions and discussion within a commission docket. They can also be readily applied to any monetized energy benefit. However, adders are rarely highly accurate due to their lack of rigorous analysis and research, and therefore incur a risk of over- or under-estimating the total value of the economic impact.

Rhode Island developed a multiplier to estimate the economic development impacts of the 2014 National Grid Energy Efficiency Program Plan. According to ACEEE’s Policy Brief, multipliers were developed from an input-output model (REMI) to quantify the number of economic benefits to Rhode Island. Modeled results: For every $1 million spent on efficiency programs, the state’s GDP (gross domestic product) would increase by $3.4 million, and 36.5 jobs would be created. The multiplier adopted ultimately accounted for any double counting of benefits and costs, recognizing that some impacts (e.g., customer savings), were already accounted for in the jurisdiction’s newly developed Rhode Island Test (see RI Case Study for details). As such, National Grid uses the multiplier to account for only the economic benefits associated with the construction and implementation of energy efficiency programs.

In general, once developed, multipliers are easy to apply to a BCA. But Rhode Island’s development of a multiplier speaks to the complexity of deriving such a number. Multiple rounds of economic analysis and extensive research may be needed for a multiplier that: 1) describes all desired aspects of economic development, and 2) can correctly be applied to a BCA framework and maintain the integrity of the test (not double-count any impacts).

__________________________________________________________________________________

Importance of Symmetry in Benefit-Cost Analysis

The NSPM for DERs (NSPM) provides a comprehensive benefit-cost analysis (BCA) framework, including a set of foundational principles, that guides jurisdictions to develop (or modify) their cost-effectiveness test that reflects their specific policy goals.

Principle 3 of the NSPM for DERs highlights the importance of symmetrical treatment of benefits and costs in benefit-cost analysis. This means that if benefits of one impact is accounted for, then costs of that impact should be accounted for, too. In the case of economic development, if jobs created by an efficiency program are included in BCA, then jobs lost from e.g., the power generation industry should be included as well. In any BCA, it is important to account for net jobs.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Wait, there’s another state we should mention…

Recently, Illinois conducted an economic development analysis to help inform how its EE programs contribute to meeting its Future Energy Job Act goals. As described for Rhode Island, they can be used to develop multipliers or simply used to inform states about the impact of EE programs on their economy. Illinois’s study was conducted using the IMPLAN input-output model. Modeled results show that around 18,000 jobs will be created, with $1 billion in labor income, and nearly $3.6 billion added to state GDP as a result of the EE programs. However, there are no plans to include these numbers in the BCA due to the potential double-counting of benefits, and it is unclear how this information will be used to inform efficiency investments.

Input-output models are much more sophisticated and accurate than an adder or multiplier. These models calculate direct, indirect, and induced jobs separately, making them more detailed than other quantification methods. They typically answer questions related to the amount of revenue needed to support a worker for a year or to create a single dollar of GDP. As you might expect, such rigorous modeling analysis is more expensive than using an adder or multiplier.

Deciding on Qualitative or Quantitative Inclusion of Impacts in BCAs

The NSPM for DERs recommends that economic development be included separately from a program’s primary BCA (see Chapter 4). There are many ways economic development impacts can be expressed (e.g., job-years, GDP, personal income, state tax revenues), and it is difficult to derive an accurate number for their net impact. These terms of expression are too interrelated and overlapping, so a jurisdiction “cannot simply take the sum of them… to derive the net impact” (NSPM, Appendix B). GDP and state tax revenues are representative of economic activity in a state rather than impact on society or a customer in an energy efficiency program. Thus, they represent a different kind of economic analysis and should not be added to the monetary BCA results. As such, it is most useful to present this information alongside the primary BCA.

In some cases, job benefits can be quite large and can impact the determination of cost-effectiveness. This raises the question “to what extent should economic impacts – even if clearly articulated as a policy goal – be used to justify investment in DER(s) when the impact far outweighs the energy impacts e.g., avoided energy/capacity costs?”

If a program is marginally cost-effective, but creates thousands of jobs, regulators may be more inclined to approve the program. However, if jobs and economic development account for most of the benefits of a program – whereby the job impacts dominate the primary goal of the program e.g., reducing energy use – then economic development benefits can unduly overwhelm the monetizable, energy-related benefits and costs. This situation requires careful consideration to ensure appropriate alignment of impacts with applicable policies.

Closing Thoughts

The NSPM is clear that a jurisdiction’s primary cost-effectiveness test should account for its relevant policy goals. So, if a jurisdiction has identified economic development as a goal for any DER investment, then the first step is to ensure that it will be part of the jurisdiction’s primary test.

The next step is for the commission to determine how best to analyze such impacts, which will depend on things like available budgets and resources, and desired complexity and accuracy of the selected quantification approach or method. Ultimately, qualitative consideration of an economic impact assessment is a sound approach to apply to BCA results, as recommended in the NSPM. It would be easier if cost-effectiveness testing was a clear-cut process. Benefit-cost analysis can in some cases be more of an art than a science when considering certain impacts.

What we can all agree on, however, is that if a jurisdiction has identified economic development as a goal for DER investments, then such impacts should be considered – even if qualitatively – because the value is not zero. Especially now, with the need to recover jobs lost during the pandemic and to create new jobs in the context of clean energy growth, accounting for economic development in BCA is as important as ever.

–Julie Michals is Director of Valuation and Shayna Fidler is Research Associate at E4TheFuture; Devin Hubbard is an intern.